Current thinking as of March 2023

Despite our slow increase in Portuguese membership, it might be fair to say that not a lot has been happening with Rethinking the Medieval Frontier over the last few months; what with the general situation of UK higher education, research time has been extraordinarily hard to come by and, indeed, for some of us at the University of Leeds, explicitly cancelled. But they can't stop us thinking! And so I thought I'd just write something quick about what that thinking is currently looking like. Then I guess I'll find out whether any of my managers read this...

Learning

In the first place, I have been reading still, even if only on the train to and from work, without time to process the notes, or where I could justify it as part of my teaching. That's meant a few frontiers-related things passing before my eyes, and I can say a little bit about them.

- Peter Linehan,

At the Spanish Frontier

, in The Medieval World, ed. by Peter Linehan and Janet L. Nelson, Routledge Worlds, 1st edn (London: Routledge, 2001), pp. 37–59. - Enrique Rodríguez-Picavea,

The Kingdom of Castile (1157–1212): Towards a Geography of the Southern Frontier

, trans. by Andrew Edwards, Mirator, 7 (2005), 1–18 <http://www.glossa.fi/mirator/pdf/frontiersofcastile.pdf> [accessed 3 January 2023]

I know there is a second edition but it isn't on my shelves, so. The big thing I got from this other than enjoyment, because reading the sadly late Dr Linehan is always enjoyable in my experience – he started one late sentence, For the average peninsular sheep...

– is the idea that the medieval Iberian frontier was just too big and too empty for any coherent policy to work out there because of manpower shortage, so that we frequently find practice contradicting ideals: [on the frontier]… only rarely did theory and practice, whether Islamic or Christian, ever precisely coincide, or even get on. There, all that was to be got on with was life itself.

He also had some effective attacks on the idea of seeing the Iberian frontier in Turner's terms, and unlike many he did actually seem to mean Turner as Turner actually wrote, as tested out by Archibald Lewis, Robert I. Burns and Lawrence McCrank, all of whom got their time under the critical spotlight as a result.1 It's unfortunate that so important a set of critiques were crammed away into a tiny part of an oddly-judged textbook, but at least I have now found them...

This is rather less use, despite Rodríguez-Picavea being someone I have otherwise always found useful.2 The paper attempts to categorise the geographical spaces of the Castilian frontier, and that's about it; the categories are arbitrary and poorly-defined, and while it goves some environmental context for the conflict between Castile and Almohads that might explain some military details, I couldn't honestly say I see why the author undertook this study.

I'd love to say there was more than that, and in fact there are a couple of things in my file, but I can't get anything out of them for this post.

Thinking

So just now I am thinking mostly with what I already had in hand and with what I last presented on, back at the International Medieval Congress just gone. In those terms I have been thinking, not least because of a book I'd like to write, primarily about the ability of individuals to influence or change their socio-political circumstances. In theory, the frontier is a better place to do that than the centre of a polity, unless one has very privileged access at least, and even then change is easiest along certain lines which reinforce the instantiated hierarchy at the centre. At the edge, where the centre has less grip and where alternative centres may be available, that bar for agency is much lower, or so it seems to me.

Statue bust of Mūsā ibn Mūsā "el rey del Ebro", in modern Tudela, image by Arenillas, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons>

So I have been trying in my last few papers to substantiate that by looking at how local powerful men (and women—fewer, far fewer, but never absent) worked a frontier situation to their advantage. At first I looked at people who used their ability to connect the edge to the centre to get things from the centre. This was ultimately a dangerous game to play; the relationships seem to have needed perpetual renegotiation, because I guess they were non-standard but also and more often because, typically, the position of broker-to-the-centre was contested. Thus the Banū Qāsī warlords of the ninth- and tenth-century Ebro valley (set into prominence by Mūsā ibn Mūsā there above) ultimately lost their position partly because of a lineage change beyond them, in the kingdom of Pamplona for whose membership of Muslim Iberia they had previously been the agents, but mostly because the frustrated centre backed a rival lineage, the Tujībids, who then became nearly as irremovable in their turn. Their own internecine fighting didn't help, though.3 Likewise, the careful use of limited patronage by Emperor Romanos I of Constantinople among the lords of Taron in the Caucasus was mainly effective because they all wanted the same piece of family privileged property in Constantinople and were willing to sell each other or themselves out for it.4

Estanislau Garcí, Ibn Marwan al-Yilliqi, bronze, Badajoz, 2003, image by Gianni86 – Trabajo propio, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Then I considered people who used a frontier location as a safe place to defy the centre. Even this, sometimes, involved negotiating a relationship with it: the supposed founder of Badajoz, `Abd al-Rahmān al-Ŷillīqī, actually got where he did by terrorising the already-existent city from a nearby fortress, from which the contemporary Andalusī state had to admit it hadn't the power to remove him, but even that then involved negotiating a peace which, while leaving the Emir no more in control than before, still let Badajoz and its environs count 'inside' the Emirate and let al-Ŷillīqī enjoy his position in peace.5 My final and maybe weirdest example of one of these edge-lords (if you'll permit me) was Saint Columba, who despite being a discredited exile from Irish high politics managed, by obtaining the use of an island from either the Picts or the Gaelic-speakers of Argyll whom we tend to call Scots even in the sixth century, and (apparently) protected there by either tremendous gossip networks and probably carrier pigeons or (as contemporaries saw it) something like second sight, managed, because unreachable and uncommitted, to interfere in far more kingdoms' politics, succession and so on than he ever could have done by staying put.6 All of these people played their games very well; but they could only play them like that from the frontier.

Remains of San Juan Bautista de Trevejo, in the province of Cáceres, a pretty cut-off location before the thirteenth century and at least looking like the sort of thing I'm talking about, whether it was that or not. Image from Trevejo, la última aldea del medievo extremeño

, Escapada Rural Mag, 12 January 2022 <https://www.escapadarural.com/blog/trevejo-la-ultima-aldea-del-medievo-extremeno/, believed fair use from their Condiciones de uso

The group I would most like to be able to consider, of course, is the third one, those who simply preferred not to engage with the centre at all. The problem is of course that the records are almost always the centre's. Archæology should help, and it does, but if a group is actually completely cut off, that tends to mean we have no useful comparators for their material culture, thus making it almost impossible to date stylistically. Slowly, radio-carbon dating is fixing this even for anonymous peasant settlements, and we're finding that all kinds of things don't belong when we thought they did ("Visigothic" churches for just one example).7 But I suppose it's also a question worth raising whether such a group is even on a frontier; the very concept seems to imply a relationship with somewhere else which that group wouldn't have had. If nowhere else thought they did either, then they're arguably not at an edge but their own centre.

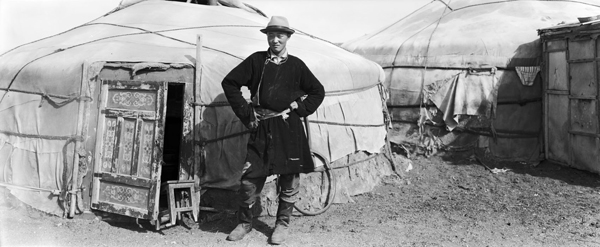

Mongol uls, image by Lois Conner, 1997, taken from Owen Lattimore, On the Wickedness of Being Nomads

, China Heritage Quarterly, 19, September 2009 <http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/articles.php?searchterm=019_nomads.inc&issue=019>, no copyright visibly asserted

One might, of course, reasonably ask how many such groups there have ever been given humanity's seemingly eternal tendency to wander around, and all the examples I can quickly think of occupied marginal spaces whose economy they held up at least partly by engaging in a limited fashion with the organisations at their edges, not therefore being complete isolates as the proposition requires.8 Thus it was, for example, that young Owen Lattimore could trek across the deserts of Central Asia with Mongolians and consider their peculiarly non-aligned situation between the states of Russia and China which would eventually manage to swallow them; he could do that because they were nonetheless trading with people from outside and he was a trader from outside.9 Is that just because that kind of grouping only gets recorded when an outsider, be they independent or political, gets involved? I have been very interested in what how a political actor begins that development, after all.10 Or is it actually that most people are in some kind of contact with other people and what I'm setting up here is basically a lost people out of some boy's-own-explorer novel rather than a thing which really happens?

A real-life case of the boy's-own explorer: Edward Marriott, The Lost Tribe (London: Pan Macmillan 1996)

I don't have answers to these questions as yet, but then this post didn't promise them; it just promised a snapshot of my current thinking, and that is pretty much what you have here. If you also have thoughts, I would love to hear them, though since the University of Leeds won't let me open up comments here it'll have to be by e-mail. In the meantime, there is beginning to be the hope of further news of Rethinking the Medieval Frontier activity, so hopefully I'll be back before long to tell you about that!

1. The works he attacked being, respectively (pp. 38 & 46-50) Archibald Lewis, The Closing of the Mediaeval Frontier 1250-1350

, Speculum, 33.4 (1958) <https://doi.org/10.2307/2846901>; (pp. 50-51) Robert I. Burns, The Significance of the Frontier in the Middle Ages

, in Medieval Frontier Societies, ed. by Robert Bartlett and Angus MacKay (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989), pp. 307–30; and (also pp. 50-51) Lawrence J. McCrank, The Cistercians of Poblet as Medieval Frontiersmen: An Historiographic Essay and Case Study

, in Estudios en homenaje a Don Claudio Sánchez-Albornoz en sus 90 años: Anexos de Cuadernos de Historia de España, 6 vols (Buenos Aires: Instituto de Historia de España, Universidad de Buenos Aires, 1983), ii, 313–60. This last got special treatment because it had Linehan's own earlier work in its sights, a paper from a conference in 1974 which McCrank cited as being by Burns but which was actually, as Linehan pointed out here (in At the Spanish Frontier

, p. 54 n. 11) by him and never published (despite the bibliographical particulars helpfully provided by McCrank

, ibid.). That lack of publication may explain McCrank's apparent confusion over what Linehan had in fact said, gently pilloried by Linehan ibid. p. 50: If this and the counter-argument (if that is what it is) are indeed what I meant then I can only agree with Dr McCrank....

2. Especially Enrique Rodríguez-Picavea, The Frontier and Royal Power in Medieval Spain: A Developmental Hypothesis

, trans. by Andrew Edwards, The Medieval History Journal, 8.2 (2005), 273–301 <https://doi.org/10.1177/097194580500800202>.

3. The main source here I used here is La Marca Superior en la obra de al-`Udrí

, trans. by Fernando de la Granja, Estudios de la Edad Media de la Corona de Aragón, 8 (1967), 447–545 <https://www.condadodecastilla.es/articulos-de-investigacion/la-marca-superior-la-obra-al-udri/>; for wider commentary see especially Jesús Lorenzo Jiménez, La dawla de los Banū Qasī: origen, auge y caída de una dinastía muladí en la frontera superior de al-Andalus, Estudios Árabes e Islámicos: Monografías, 17 (Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 2010).

4. The main source here is Constantine Porphyrogenitus, De administrando imperii, ed. Gyula Moravcsik & transl. Romilly J. H. Jenkins, rev. edn. (London: Athlone Press, 1962), repr. as Dumbarton Oaks Texts 1 (Washington DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1967, reprinted 1993 and 2008); no-one really covers this in depth but see Steven Runciman, Cc. 43-46/165

, in

Constantine Porphyrogenitus, De Administrando Imperii: a Commentary, ed. by Romilly J. H. Jenkins (London: Athlone Press, 1962), repr. as Dumbarton Oaks Texts 4 (Washington DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collections, 2012), pp. 156-180 and T. W. Greenwood, Armenian Neighbours (600‒1045)

, in The Cambridge History of the Byzantine Empire c. 500‒1492, ed. by Jonathan Shepard (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), pp. 333–364 <https://doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521832311.015>.

5. Here the main source is Muḥammad ibn `Umar Ibn al-Qūṭīyah, Early Islamic Spain: The History of Ibn al-Qutiya, trans. by David James (London: Routledge, 2011) <https://archive.org/details/early-islamic-spain-the-history-of-Ibn-al-qutiyah>; for commentary see Eduardo Manzano Moreno, La frontera de al-Andalus en época de los Omeyas, Biblioteca de historia, 9 (Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 1991), pp. 184 and 195–204, and Ann Christys, Crossing the Frontier of Ninth-Century Hispania

, in Medieval Frontiers: Concepts and Practices, ed. by David Abulafia and Nora Berend (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2002), pp. 35–53 <https://www.academia.edu/2087228/Crossing_the_Frontier_of_Ninth-Century_Hispania> (pp. 46–47).

6. The main source is naturally Adomnán, Adomnán's Life of Columba, ed. by Alan Orr Anderson and Marjorie Ogilvie Anderson, Oxford Medieval Texts, 2nd edn (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991), though the best commentary to my mind is the notes in the alternative translation, Adomnán of Iona, Life of St Columba, trans. by Richard Sharpe, Penguin Classics (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1995). For a monographic study see Tim Clarkson, Columba (Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2012).

7. On the controversy over "Visigothic" churches see Mickey Abel, Strategic Domain: Reconquest Romanesque Along the Duero in Soria, Spain

, Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture, 2.2 (2007), 1–57 <https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol2/iss2/2/>, Alexandra Chavarría Arnau, Churches and Aristocracies in Seventh-Century Spain: Some Thoughts on the Debate on Visigothic Churches

, Early Medieval Europe, 18.2 (2010), 160–74 <10.1111/j.1468-0254.2010.00294.x>, and now Francisco J. Moreno Martín, ¿Adónde han ido las iglesias visigodas? Una nueva historia de la arquitectura altomedieval

, in La primera mentira: Mitos y relaciones distorsionados en la enseñanza de la Historia, ed. by Daniel Jiménez Martín (Madrid: Postmetropolis, 2021), pp. 159–76 <https://www.academia.edu/88079463/_Adónde_han_ido_las_iglesias_visigodas_Una_nueva_historia_de_la_arquitectura_altomedieval.

8. I found not so long ago that the conviction that people will just migrate whatever happens is so deep that there is something like a genuine debate over whether people might have first reached the Americas over the Atlantic ice-sheet during the Ice Age: the two most recent elements of the exchange are James W. P. Walker and David T. G. Clinnick, Ten Years of Solutreans on the Ice: A Consideration of Technological Logistics and Paleogenetics for Assessing the Colonization of the Americas

, World Archaeology, Debates in World Archaeology, 46.5 (2014), 734–51 <https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2014.953708>, and Stephen Oppenheimer, Bruce Bradley and Dennis Stanford, Solutrean Hypothesis: Genetics, the Mammoth in the Room

, ibid., 752–74 <https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2014.966273>, with references to earlier ones. For more nuanced and period-relevant work see Johannes Preiser-Kapeller, Migration

, in A Companion to the Global Early Middle Ages, ed. by Erik Hermans (Leeds: ARC Humanities Press, 2020), pp. 477–509 <https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvz0h9cf.23>, or Johannes Preiser-Kapeller, Lucian Reinfandt and Yannis Stouraitis, Migration History of the Afro-Eurasian Transition Zone, c. 300–1500: An Introduction (with a Chronological Table of Selected Events of Political and Migration History)

, in Migration Histories of the Medieval Afroeurasian Transition Zone: Aspects of Mobility between Africa, Asia and Europe, 300–1500 C.E., ed. by eidem, Studies in Global Social History, 39 (Leiden: Brill, 2020), pp. 1–49 <https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004425613_002>.

As for the uncontrolled spaces, there is of course famously James C. Scott, The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia, Yale Agrarian Studies (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009) <https://law.yale.edu/system/files/documents/pdf/Intellectual_Life/LTW-Scott.pdf>, to which cf. Jean Michaud, Zomia and Beyond

, in Routledge Handbook of Asian Borderlands, ed. by Alexander Horstmann, Martin Saxer, and Alessandro Rippa (London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2018), pp. 73–88; but even Scott's Zomia is interesting to him because it can resist outside intervention – it wouldn't be interesting to him if there were no attempts to impose upon it. For an application of Scott in a medieval frontier context see Nicholas S. M. Matheou, Hegemony, Counterpower & Global History: Medieval New Rome & Caucasia in a Critical Perspective

, in Global Byzantium, ed. by Leslie Brubaker, Rebecca Darley, and Daniel Reynolds, Publications of the Society for the Promotion of Byzantine Studies, 24 (presented at the Fiftieth Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies, University of Birmingham, 25-27 March 2017, London: Routledge, 2022), pp. 208–36.

9. On Lattimore's fascinating, if arduous, career, see William T. Rowe, Owen Lattimore, Asia, and Comparative History

, Journal of Asian Studies, 66.3 (2007), 759–86. His most relevant works to this issue are Owen Lattimore, The Desert Road to Turkestan (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, and Company, 1929) <http://pahar.in/pahar/1929-the-desert-road-to-turkestan-by-lattimore-s-pdf/ and idem, Mongol Journeys (New York City, NY: Doubleday, Doran and Co., 1941), though one should probably also cite idem, Inner Asian Frontiers of China, Beacon Paperbacks, 130, 2nd ed. (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1962) <https://faculty.washington.edu/stevehar/Lattimore.pdf> and idem, Inner Asian Frontiers: Chinese and Russian Margins of Expansion

, Journal of Economic History, 7.1 (May 1947), 24-52, <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050700053432, reprinted as Inner Asian Frontiers

in New Compass of the World: A Symposium on Political Geography, ed. by Hans W. Weigert, Vilhjalmur Stefansson and Richard Edes Harrison (New York City, NY: Macmillan, 1949), pp. 262-295 and under original title in Studies in Frontier History: Collected Papers, 1928 – 1958, by Lattimore (London: Oxford University Press, 1962), pp. 134–59 <https://roxanarodriguezortiz.files.wordpress.com/2011/08/lattimore_1962-studies-in-frontier-history-collected-papers-1928-1958-by-lattimore-s.pdf>, as well as the classic Lattimore, The Frontier in History

, in Relazioni (presented at the X Congresso Internazionale di Scienze Storiche, Firenze: G. C. Sansoni, 1955), i, 105–38, repr. in Studies in Frontier History, by Lattimore, pp. 469-491.

10. Jonathan Jarrett, Engaging Élites: Counts, Capital and Frontier Communities in the Ninth and Tenth Centuries, in Catalonia and Elsewhere

, Networks and Neighbours, 2.2 (2014), 202–30 <https://nnthejournal.files.wordpress.com/2018/05/nn-2-2-jarrett-engaging-elites1.pdf>; idem, La fundació de Sant Joan en el context de l'establiment dels comtats catalans

, trans. Xavier Costa, in El monestir de Sant Joan: Primer cenobi femení dels comtats catalans (887-1017), ed. by Irene Brugués, Xavier Costa and Coloma Boada (Barcelona: Publicacions de l'Abadia de Montserrat, 2019), pp. 83–107.