Recategorising with medieval frontiers

It seems a long time since our last update here and the world has grown a little calmer, at least calm enough to be back to blaming politicians for most of what is going wrong rather than hitherto-unknown organisms.1 And truly, what with the number of extensions and policy shifts it does seem as if the teaching year no longer ends and there will never again not be marking to do of work by people whose faces one never sees; but your humble correspondent has also been trying to get this project moving again after our long down phase, and this has meant some reading at last. Trying to embody the spirit of our project, I've largely been reading around looking for people writing interesting things about frontiers in areas I don't know well, and I thought it would be interesting and maybe useful to others to share some reading notes. They can be loosely sorted into categories, and the first, pleasingly, is itself about categorisation.

Categorising Frontiers

Some years back I read an article by this man called 'From Alienation to Co-Existence and Beyond', which is about Kashmir, which I've now been revisiting. I thought and I think it one of the brightest things I've seen about modern frontiers, and this not least because it breaks out, then breaks, a categorisation, one he explicitly borrowed from one Oscar J. Martínez, whose work I haven't yet been able to look at separately but must.2 The categorisation is like this:

- 'alienated', when authorities on both sides try to prevent crossing;

- 'coexistent', when traffic across the border is regulated but not prevented;

- 'interdependent', where structures exist to facilitate and manage border-crossing;

- and 'integrated', like the Schengen Zone in Europe, where actually there's just free traffic.

I struggle with separating 'coexistent' and 'interdependent', there, but otherwise I see what it's doing and how it might be a way to sort answers to some of our project's test questions about what and who can cross a given frontier. Martínez's categorisation was developed for the US-México border and Mahapatra doesn't think it works that well for Kashmir, partly because some of the border-crossing there is actually military and insurrectionist, which Martínez apparently doesn't allow for.3 This already makes Mahapatra's version more useful for medievalists, but the other thing that does is that Martínez expects this to be a transitional categorisation that leads from step 1 ultimately to step 4, and Mahapatra understandably doubts that this is the direction of travel with Kashmir.4 Of course, neither saw Covid-19 coming but I feel like Trump's famous wall (actually started by George W. Bush and continued under Obama, did you realise?) might already have forced Martínez to rethink his teleology.5

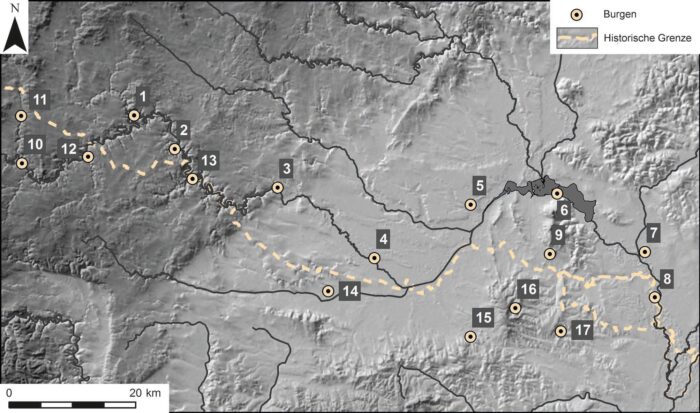

Since there are three authors here, it seems easier to represent them by their work rather than their faces... This is a map of fortress sites along the old border between Moravia and the Carolingian Empire, from Stefan Eichert, Jiří Macháček, and Nina Brundke, ‘Grenze – Kontaktzone – Niemandsland: die March-Thaya-Region während des frühen Mittelalters’, Beiträge zur Mittelalterarchäologie in Österreich, 36 (2020), 52–67 (p. 59, Abb. 6)

Then much more recently, I read some early medievalists attempting a similar exercise.6 Their categorisation is threefold: Grenz, Kontaktzone and Niemandsland, which they compare to another one by Bryan Feuer, who distinguishes 'Boundary' (linear division), 'Border' (shared zone) and 'Frontier' (exterior zone).7 It seems to me that this latter has obvious problems, mainly that it's obviously measured from only one side of the frontier, and not from within it, or you couldn't invoke the idea of 'exterior' – but I haven't read it and perhaps they're not fair to Feuer. Our authors claim that their categories match his, but actually I think they work better because of not doing that.

It is interesting, however, that these categories don't quite match Martínez's scheme either: 'alienated' could be either of Grenz or Niemandsland depending on how intense control and/or fortification was on the frontier in question, and if one took a particular view of, say, the Castilian-Granadan frontier in the fifteenth century it could be either depending on how intense you think those things need to be to count.8 On the other hand, since there were dedicated arrangements for ransoming and trade across that frontier, it might look better as either a Kontaktzone or 'coexistent'/'interdependent' space.9 And, although there was nothing like the Schengen Zone in any medieval context I know about, in so far as movement might often be pretty free but importation of goods would almost always have been watched fairly closely and strangers regarded with suspicion even well away from frontiers, the fact that this means that, say, the eastern end of the famous landward Silk Routes might qualify at once as 'integrated' and Niemandsland suggests to me that these categories need to brought up against each other and rethought.10 It's partly that it depends what aspect of the frontier you focus on, control or crossing, and lots of the modern literature seems to be fairly bewildered by the fact that crossing goes on despite control and invoke the 'territorial trap' as a get-out clause for how people don't respect arbitrary nation-state borders.11 But we can, I think, do better than this, and if using medieval examples helps show that we need to, well, we're here!

1. Obviously, academics are also blaming a lot of other people for things going wrong with the academy right now, such as our managements – see Anna McKie, '"Eulogy to Research" as Pandemic Makes Teaching the Priority', Times Higher Education (THE), 24 May 2021 <https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/eulogy-research-pandemic-makes-teaching-priority> – or our students and people who provide them with software that makes cheating easier for them – see Thomas Lancaster and Codrin Cotarlan, 'Contract Cheating by STEM Students through a File Sharing Website: A Covid-19 Pandemic Perspective', International Journal for Educational Integrity, 17.1 (2021), 1–16 <https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-021-00070-0> – or indeed journalists – see Alice Fleerackers, Michelle Riedlinger, Laura Moorhead, Rukhsana Ahmed, Juan Pablo Alperin, 'Communicating Scientific Uncertainty in an Age of COVID-19: An Investigation into the Use of Preprints by Digital Media Outlets', Health Communication, 2021, 13pp <https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2020.1864892>, you know. But the academic system arguably gives us a persecution complex anyway – see for example Bill Scott, 'Let's Blame Academics, Says a Guardian Headline', Bill Scott’s Blog, 11 December 2013 <https://blogs.bath.ac.uk/edswahs/2013/12/11/lets-blame-academics-says-a-guardian-headline/>, although for what it's worth the headline doesn't say that; Scott Jaschik, 'Stop Blaming Professors', Inside Higher Ed, 9 June 2014 <https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2014/06/10/study-finds-students-themselves-not-professors-lead-some-become-more-liberal-college>; Matt Flinders, 'Are We to Blame? Academics and the Rise of Populism', OUPblog, 6 May 2018 <https://blog.oup.com/2018/05/academics-scholars-rise-of-populism/>, with the actual attacks they're all defending against weirdly hard to find. For what's going on here, my best explanation is provided by Vik Loveday, 'The Neurotic Academic: Anxiety, Casualisation, and Governance in the Neoliberalising University', Journal of Cultural Economy, 11.2 (2018), 154–66 <https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2018.1426032>, and can be broadly summed up as 'our paymasters, not understanding what we do or what its value might be but recognising that it makes us independent by disposition, try to control us with a persistent narrative of our personal and social uselessness maintained by bureaucratic micro-aggressions', which mostly works.

2. Debidatta Aurobinda Mahapatra, 'From Alienation to Co-Existence and Beyond: Examining the Evolution of the Borderland in Kashmir', Journal of Borderlands Studies, 33.1 (2018), 141–55 <https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2016.1238316>, citing mainly Oscar J. Martínez, Border People: Life and Society in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 1994).

3. Mahapatra, 'From Alienation to Co-Existence and Beyond', pp. 146–48.

4. Ibid., pp. 151–52.

5. Margaret E. Dorsey and Miguel Diaz-Barraga, 'Beyond Surveillance and Moonscapes: An Alternative Imaginary of the U.S.–Mexico Border Wall', Visual Anthropology Review, 26.2 (2010), 128–35 <https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-7548.2010.01073.x>.

6. Stefan Eichert, Jiří Macháček, and Nina Brundke, 'Grenze – Kontaktzone – Niemandsland: die March-Thaya-Region während des frühen Mittelalters', Beiträge zur Mittelalterarchäologie in Österreich, 36 (2020), 52–67 <https://www.academia.edu/s/443486aa33>.

7. Bryan Avery Feuer, Boundaries, Borders and Frontiers in Archaeology: A Study of Spatial Relationships (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2016), discussed by Eichert & al., 'Grenze – Kontaktzone – Niemandsland', pp. 60–61.

8. See José Enrique López de Coca Castañer, 'Institutions on the Castilian-Granadan Frontier', in Medieval Frontier Societies, ed. by Robert Bartlett and Angus MacKay (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989), pp. 127–50; a study which does a lot more with this kind of data, and that I want to look at separately, is Daniel Oto-Peralías and Diego Romero-Ávila, 'Historical Frontiers and the Rise of Inequality: The Case of the Frontier of Granada', Journal of the European Economic Association, 15.1 (2017), 54–98 <https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvw004>.

9. See James William Brodman, 'Charity and Captives on the Medieval Spanish Frontier', Anuario Medieval, 1 (1989), 25–36.

10. So many things could be cited here, but try Tansen Sen, 'The Travel Records of Chinese Pilgrims Faxian, Xuanzang, and Yijing: Sources for Cross-Cultural Encounters between Ancient China and Ancient India', Education About Asia, 11.3 (2006), 24–33, which is all true but definitely taking a position; at a different position one could cite Étienne de la Vaissière, 'Trans-Asian Trade, or the Silk Road Deconstructed (Antiquity, Middle Ages)', in The Cambridge History of Capitalism, ed. by Larry Neal and Jeffrey G. Williamson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), pp. 101–24 <https://doi.org/10.1017/CHO9781139095099.005>, with Valerie Hansen, The Silk Road: A New History (New York City, NY: Oxford University Press, 2012), somewhere in between. For a sense of how impossible that landscape has been to control, however, the best resort is probably still Owen Lattimore, The Desert Road to Turkestan (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, and Company, 1929) <http://pahar.in/pahar/1929-the-desert-road-to-turkestan-by-lattimore-s-pdf/>, because he'd actually travelled it.

11. Chiara Brambilla, 'Exploring the Critical Potential of the Borderscapes Concept', Geopolitics, Borderscapes: From Border Landscapes to Border Aesthetics, 20.1 (2015), 14–34 <https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2014.884561>, p. 19.